Meet ArcticNet: Dr. Philippe Archambault

Dr. Philippe Archambault of Université Laval has been a valuable member of ArcticNet for most of the Network’s history, beginning as a Network Investigator in 2007. On April 1, Dr. Archambault and Dr. Jackie Dawson of the University of Ottawa took on the scientific directors’ roles at ArcticNet, succeeding Dr. Louis Fortier, who retired this year.

Dr. Archambault is a biology professor who studies the interaction between human activity and environmental change, and the impacts on biodiversity and the benthic environment. His research in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Canadian Arctic has spanned the intertidal zone to the deep sea, and he has provided leadership to many organizations, steering committees and advisory committees, including the Canadian Healthy Ocean Network (CHONe), FRQNT of the Innovative Network Notre Golfe and Québec Océan, the International Scientific Committee, Ocean Network Canada, and the World Congress of Marine Biodiversity 2018.

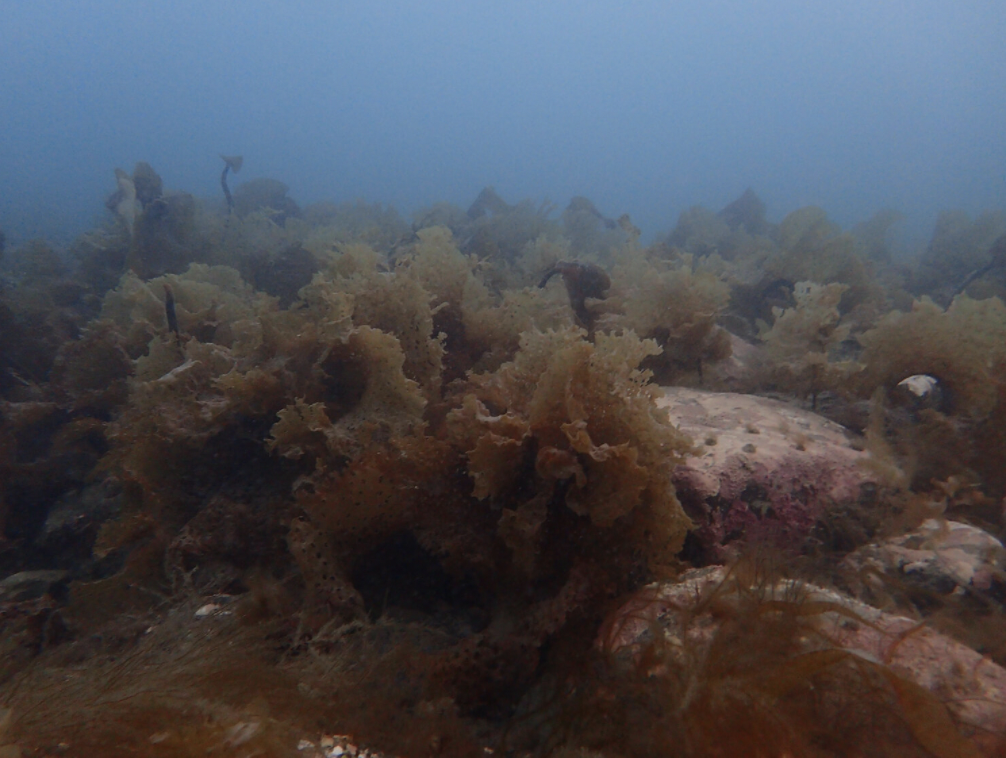

A renowned Arctic researcher, Dr. Archambault is the co-leader for ArcticNet’s “ArcticKelp” project along with Dr. Karen Filbee-Dexter, examining the fate of kelp forests in a rapidly changing Arctic. While many people associate kelp forests with more southerly regions such as the Pacific coast, Arctic kelp forests are a vital component of the northern marine ecosystem, forming unique and complex habitats housing and feeding a wide variety of species. The forests are not well known, despite being recorded throughout the Canadian Arctic; ice scour and erosion create barren terrestrial and coastal environments, and deep offshore research encountered little kelp. Move closer to shore, however, and these forests are teeming with life, sheltering biodiversity that surpasses what you find in areas without kelp.

Arctic kelp forests play a significant role in capturing carbon, similar to terrestrial forests, as well as influencing wave patterns and water currents. Understanding the ways this vibrant ecosystem may change as Arctic waters warm and sea ice melts will help northern communities anticipate, prepare for and even benefit from future impacts; it is possible that kelp forests are in fact benefiting from longer periods of light. Combined with Inuit knowledge of the coasts, Dr. Archambault’s work helps to fill a critical gap in our assessment of a rapidly-changing Arctic marine environment.

Dr. Archambault’s research is making waves throughout the scientific community: a project modelling the interconnectedness of trophic networks was named by Québec Science as one of the top 10 discoveries in 2019. Similar to the “six degrees of separation” theory—or thinking about the “friends of friends” in Facebook for a more modern example—the model found that fish species around the world are connected within three degrees of separation, and indeed as low as 2.1. The finding suggests a resilient and adaptable system, in which the decline or disappearance of one species can be compensated with others fairly easily taking up a similar ecological niche. However, this interconnection also introduces vulnerability: a localized disturbance such as an oil spill can quickly impact the entire world—a phenomenon Dr. Archambault compares to the Butterfly Effect.

With all marine species so thoroughly connected to each other, Dr. Archambault emphasizes the need for a whole-system and national approach to research and marine management. “Inuit must be part of every decision, because what happens in other ocean regions of Canada could affect their food systems,” he said. “You cannot take only a regional approach. You need a network.”

A Nation-Wide Arctic Network

With his scientific research emphasizing the need for a network approach to Arctic science, it is no surprise that Dr. Archambault has taken on the challenge of leading ArcticNet’s activities through its new phase. Working with Dr. Dawson as joint scientific directors, Dr. Archambault seeks to ensure ArcticNet grows and strengthens into the future while building on the successes of its past.

“You cannot work by yourself in the Arctic. It’s too expensive and difficult,” he said. “Network collaboration gives you far more than the sum of its parts.” By working closely with communities, centring co-creation and collaboration, and sharing knowledge between researchers, students and community partners, Arctic science is stronger and the challenges more achievable. Effecting change in a silo is nearly impossible, but by working with 32 universities, territorial, provincial, federal agencies across the country and communities throughout the North, Dr. Archambault believes there is an opportunity for true change.

“We’re there not only for northern science, but for northern peoples, and for all of Canada. It’s about making sure Inuit have the opportunity to achieve their full potential, and incorporating all different types of knowledge into our understanding of the Canadian Arctic.”