Permafrost thaw and northern infrastructure

By Heather Desserud

When a warming climate causes permafrost thaw, the changes affect the very foundations of Northern life.

In northern communities, infrastructure, buildings and transportation networks are often constructed over a permafrost base, which is vulnerable to changes to climate and rapidly warming Arctic temperatures. This can spell disaster for the structures above, damaging buildings and roads as the permafrost degrades beneath. Permafrost thaw also releases damaging contaminants into the ecosystem, impacting food chains and community health.

Dr. Fabrice Calmels is the Research Chair of Permafrost and Geoscience at Yukon University, investigating the impacts of climate change on the Canadian landscape. Dr. Calmels and co-investigators Drs. Pascale Roy-Léveillée (Laurentian), Michel Allard (Laval) and Duane Froese (Alberta) lead the ArcticNet-funded project, “Supporting humans in a thawing landscape,” which takes a multidisciplinary, networked approach to studying permafrost changes in the North. Working with geography and earth sciences researchers across Canada, the project emphasizes collaboration with communities, territorial governments and stakeholders across Northern Canada to study the impact of climate change on highways, land management, and food networks. The team also studies the vulnerability of traditional lands to hazards related to permafrost degradation and changes in hydrology caused by climate change. Dr. Calmels and Dr. Léveillée have worked with the Vuntut Gwitchin Government to study the sensitivity of culturally important areas to permafrost thaw, impacts on water quality, and changes in hydrology, as well as contribute to Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation’s community-monitoring program.

Permafrost thaw is a serious concern for communities: understanding the rate of thawing and the ways it could progress in future will help with engineering issues for those seeking to build new infrastructure, food security for those relying on country foods that could be contaminated by the permafrost thaw, and disaster response and mitigation plans for infrastructure already in place. When a community needs to build new housing or other buildings, understanding the risks associated with planned sites and incorporating the necessary mitigation strategies reduces long-term cost and potential harm from permafrost thaw. Anticipating areas of highway at risk can help transportation engineers plan new routes or identify at-risk sections for increased monitoring.

Dr. Calmels in partnership with Dr. Allard researches high-risk and high-importance sites at the Nunavik Airports (Quebec), Iqaluit Airport (Nunavut), and along the Alaska and Dempster Highways (Yukon) to test new embankment designs and other mitigation techniques. The team is also experimenting with innovative technologies such as CT-scanning to better understand the fundamental processes that take place when permafrost thaws with Dr. Froese. Their goal is to give communities across the Canadian Arctic the land management tools they need to analyze risk and implement mitigation techniques for safer, more resilient community infrastructure and planning.

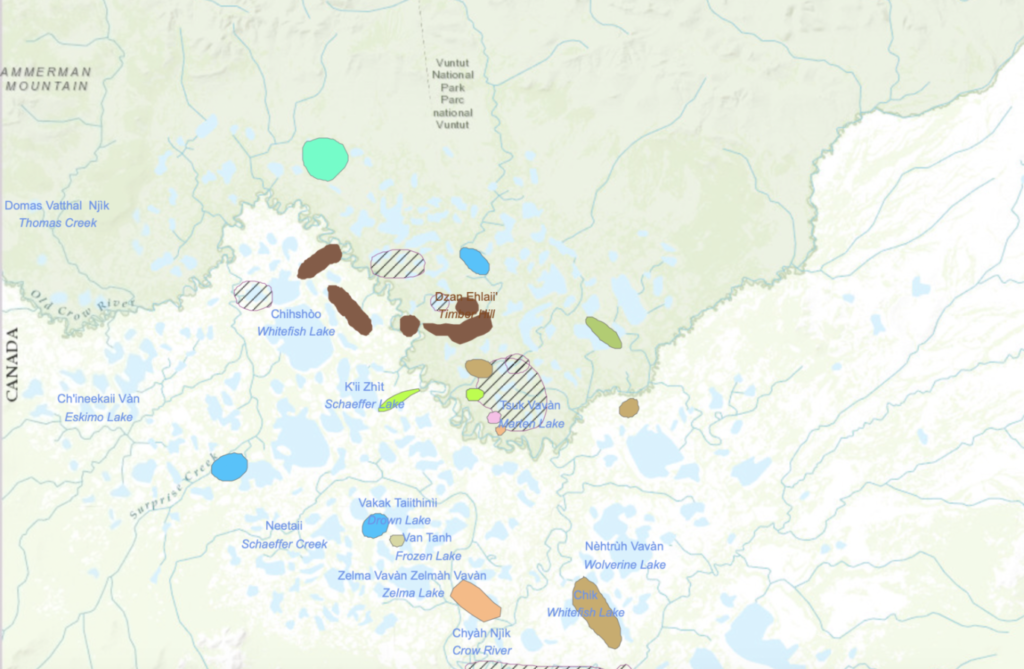

Getting the research into the hands of those who need it is a significant focus for Dr. Calmels and his team. Communities are undergoing increasing development, and some regions have no choice but to build on permafrost despite the risks. Examples of knowledge mobilization strategies include an interactive map that can help to identify areas of risk, and guide selection of sites for geotechnical engineering assessments, thus reducing costs and increasing efficiency. The tools empower the community to make decisions with the full picture in view, reducing guesswork and enabling adaptation and remediation strategies to be part of the process from the beginning. Another application of the research is identifying potential problem sites along highways at risk such as the Alaska and Dempster highways that governments can then select for remediation. Through the project’s research, a geohazard alarm system is being designed that will enable alerts and highway closures in near-real time.

When asked to describe the benefits of his research, Dr. Calmels was clear: “We are seeking to help communities increase security and save money; if you know the risks and geohazards, you can plan ahead and design the best possible remediation,” he said. “It can take many years, but at the end of the project we better understand permafrost and can make tangible recommendations, which the engineers take over and implement.”

He continued, “But you need the science first; you have to fund research to be able to support the land use plans.” Both fundamental and applied research are key to understanding the complexities of permafrost and its impacts on northern infrastructure. Dr. Calmels identified the role of ArcticNet as a connected Network as an integral part of the project’s success: “There is a lot of modelling, remote sensing, and applied research taking place across Canada; we collect our facts from many different disciplines and apply what we learn to real world situations so that we can provide solutions now, not 20 or 30 years in the future. ArcticNet helped to connect all these different projects and make them more collaborative and efficient.”